Thanks for joining us!

Day 1: Hierarchy

There are many smaller and larger cultural differences with Germany, but one literally stands out: hierarchical relations are steeper in Germany than in the Netherlands.

It really is true: in Germany, people say “Sie” much more often and for much longer than in the Netherlands. In more conservative companies, it can even happen that after thirty years of being co-colleagues, you wish a good pension to mister “Herr Müller”. This is unthinkable in the Netherlands, where even the director is quickly called with the informal ‘je’ and ‘jij’. Never start off by greeting a German prof. dr. dr. with less than a formal “Sie”. [GAE1] And possibly, you will have to add all academic titles on top. By addressing someone with ‘Sie’ (always with a capital letter!), from a German angle you show respect and grant autonomy and status to your counterpart. This has little to do with liking and appreciating someone – you can have a click with someone and still say ‘Sie’. There is also a clearly defined transition from ‘Sie’ to ‘Du’: the higher in rank, the older in age or, in a customer-supplier relationship, the customer formally proposes to say ‘du’ in the future. This is called “das Du anbieten” and can be also framed as “also, ich bin Peter” (introducing oneself with the first name is a code for stepping towards the informal “du”). Also in Germany, there is a shift towards more frequent “du”.

Don’t put your light under a bushel

In other words, in Germany you can, no, sometimes you have to stick your head out above the parapet. A Dutch “do maar gewoon, dat is al gek genoeg” (just behave normal, that is already crazy enough) will not get you anywhere in Germany. German society is more assertive and competitive – good performance is appreciated and can be shown. Status symbols such as big cars, but also academic titles are a sign of success and inextricably linked to a person’s name. Does your German colleague, manager or business partner have a Dr. title? Then it is important to address him or her as ‘Herr Doktor’ or ‘Frau Doktor’ respectively. Still, here we are talking about Germany from a Dutch perspective. To Polish or Austrian people, the usage of titles in Germany might even seem underdeveloped and much less rigid than what they might be used to.

Extra: Background information

In Germany, professional and working life are more separate than in the Netherlands, and professionalism at work is highly valued. This is related to cultural-historical developments (more on this tomorrow). It is partly influenced by church reformer Luther with his doctrine of an ‘inner’ and an ‘outer’ realm. Inwardly, good Christians concentrated on their private lives and their spiritual wellbeing; outwardly, they concentrated on their work and its content. Also in the rather “catholic” Rhineland, we can still see this separation in society, where work and private life are clearly more sharply separated than in the Netherlands. A visible example of this are the shutters that often hide private life in German homes from people on the streets. Whereas in the Netherlands, you have more people sitting towards the streets, with the interior of their house fully visible to an outsider. Protestant church reformer Calvin was important to introduce this transparency in the Netherlands, as to him, propper Christians would not have anything to hide from anyone. This also influenced the rather “catholic” Limburgans in the Euregio Meuse-Rhine.

Have a nice day and see you tomorrow (Day 2)!

By loading the video, you agree to YouTube's privacy policy.

Learn more

Day 2: Decision-making and meetings

Today we’re going to take a closer look at the steeper German hierarchies. These not only affect the German way of dealing with each other, but also the decision-making and meeting culture.

Decisions are usually taken top-down in Germany. Your decision-making authority is therefore more limited than you might be used to in the Netherlands. Subordinate departments often cannot assume final responsibility; in many cases, this lies with the top management. Decision-making procedures, therefore, often take longer and involve more people in an institutional ping-pong. Take more time into account and make sure you know how the procedures work.

Meetings – prepare yourself well

Meetings are not quite the same in Germany, and words like “overleg”, “vergadering”, and “onderonsje” are not fully equivalent to the German “Besprechung”, “Treffen” or “Rücksprache” . In Germany, meetings are often based on an agenda, which is drawn up in advance, announced and adhered to – changes to this pre-defined structure during a meeting are not as popular in Germany. There is less room for brainstorming and informal exchange of ideas and more focus on finding solutions to concrete problems. Once problems have been solved and decisions made, they are usually not challenged. “Progressive insight” as the Dutch call their more flexible approach is largely unknown in Germany.

Employees are expected to have read through the meeting documents in advance and to be thoroughly prepared. This improves the efficiency of meetings, which is why German meetings are more structured and shorter.

The seating arrangement at the German conference table often reflects the hierarchical relationships: in the middle sits the director or the person who makes the decisions, with his or her assistant on one side (usually the right-hand side) and an expert on the other – these people do not have decision-making powers, by the way. So the division of roles is visible at a glance. This is not only clear, but also makes Germans feel good as expectations are somehow explicit in such a setting.

Extra: Background information

In the Netherlands there has always been a pragmatic approach to hierarchies. This goes back to the struggle against water, in which difference between rank and file was of secondary importance. Later developments such as the strong bourgeoisie and protestant Calvinism reinforced this trend. Dutch hierarchies tend to be as flat as the landscape or even below sea level. The southernmost, hilly Limburg is actually perceived as more hierarchical compared to the rest of the Netherlands.

In Germany, the nobility built castles on hills throughout the landscapes and was less vulnerable to what happened below. It kept more power and influence and the bourgeoisie was significantly weaker. Furthermore, the German need for structures and order plays a role (more about this on day 6). Hierarchies provide a sense of security and a working environment where everyone knows where he or she stands. Finally, Prussian discipline and obedience played a lasting role. It was greatly pushed in a large army, but also during the upcoming industrialisation in the 19th century.

Have a nice day and see you tomorrow (day 3)!

Day 3: Leadership

Take a seat, have a cup of coffee or tea – we’re continuing our journey of discovery into German working culture. Today’s topic is ‘Leading and being led’.

First of all, please answer the following questions in your mind:

- How do you address your manager: with your first name or with ‘Mr’ or ‘Mrs’ plus your last name and possibly your academic title?

- Do you expect your manager to come to the office casually dressed or in an expensive suit or costume?

- How would you feel if your manager came to the office in an Audi A8 instead of on a bicycle?

- Do you feel comfortable with clear instructions on what to do, or do you expect your manager to give you the space to work independently?

Your answers will depend not only on your personal preferences, but often on your culture as well.

The role of superiors in Germany

Your manager sits at a separate table in the canteen with other managers during the lunch break and separate from other employees – a strange idea? Not so in Germany. On the other side of the border, the distance between managers and employees is greater than in the Netherlands. The brand and size of the car, the size of the office and the furnishings often indicate who is in charge. The more conservative the sector or organisation, the more clearly status and the associated status symbols are visible. Many people in Germany would criticise this, but it is still somewhat acknowledged as signs of success. Although shifts take place in start-ups and the creative sector and non-profit companies. the majority of companies and organisations in Germany are more hierarchical than in the Netherlands.

German executives are decisive, analytical and persistent. They not only set the broad outlines and take decisions, but also provide clearer leadership than their Dutch colleagues: they structure and monitor their employees’ work more tightly. In short: he or she is more the ‘boss’ who makes the decisions – and expects their employees to follow them.

Competent bosses instead of coaches

This is also due to the fact that German executives are often specialists in a particular field and have been given leadership roles over time. They are knowledgeable – German employees therefore expect their manager to be able to answer (technical) questions. In this respect, they have different expectations of their managers than Dutch employees, for whom this aspect is usually not so important. In terms of professional knowledge, German managers rely less on their employees than Dutch managers do.

Different leadership style – different expectations

German managers therefore have different expectations of their employees and conversely German employees have different expectations of their managers. This of course has consequences for the interaction and communication (more about this tomorrow), which is less ‘at an eye-to-eye level’ than used in the Netherlands. The emphasis is less on consensus and shared decision-making, which means that there is also less room for discussion.

Whether it’s the management style or something else, different expectations are a source of misunderstanding. This also applies within your own culture, of course, but especially when you work with people from another culture. So if something seems strange to you, first check your own expectations. In this way, you can see misunderstandings in a different light or from a different angle.

Have a nice day and see you tomorrow (day 4)!

Day 4: Visible or invisible - culture as an iceberg

What is culture?

There are all kinds of definitions of culture and metaphors to describe culture. They have one thing in common: they assume that only a small part of a culture is visible. These are, for example, the shutters on the windows, the slightly different fashions or less people on bikes. However, a much larger part of a culture is invisible. These are the norms, the values, the mentality. These are historically grown, deeply anchored and passed on – consciously or unconsciously – from generation to generation. So they are not innate, but learned.

Even if mentality is something we acquired, it heavily influences how we perceive the world around us and how we do things. And: Our way of seeing the world feels so normal and “natural”. In case you lived in the Netherlands for some time, you might have also acquired parts of the “Dutch way of life”. An informal tone towards you boss and “harsh” and open, Dutch criticism might have become a normality to you. When you start working in Germany, you might be confronted with a different way, and. The rules of the game that you once learned to get things done smoothly no longer work. In Germany, the rules of the game are simply different. We will raise some of them in the upcoming days.

Two models to go beyond the surface:

Text to picture] Like an iceberg, only a small part of a culture – our behaviour – is visible; the larger part – our norms, values and mentality – is invisible, but it influences the visible part.

Step out of your comfort zone

Getting to know another culture is like a little journey of discovery. A new, unknown challenge awaits you at every corner. What is entertaining when reading this mini-course, can in reality be quite exhausting. It takes a while to get used to a different way of doing things. During this period you may feel uncertain, confused or even stressed. They call this scientifically studied phenomenon ‘culture shock’. Rest assured: it is nothing you need to worry about! It happens to everyone who is going to work or live abroad. And even if you lived abroad several times already.

Culture shock – an emotional rollercoaster

Culture shock consists of 5 phases, which are usually depicted as curves:

In the first phase, euphoria is dominant. You are looking forward to your new job, perhaps also to moving to the other country. Expectations are high, you look at everything through rose-coloured glasses.

In the second phase, the culture shock phase, you feel increasingly uneasy. The novelty is gone, the first misunderstandings arise. You might realize, that your glasses where not only rose-coloured. They actually have the colours of your previous context or country, and you still see things from a previous angle. Doing things other than what you perceive “normal” is an irritation, and it just seems “wrong”.

In the third phase, the acculturation phase, things start to improve. Experiences are put into perspective and the high expectations from the early days become more realistic. You begin to adjust to the other culture. Your glasses took a little of new colour.

In the fourth phase, the equilibrium phase, everything gradually falls into place. You feel more and more at home in the other culture and integrate it into your daily life. Your glasses allow you to see the things around you more and more sharply.

The fifth phase is the return-culture shock is when you return to your previous country. For example because you are going to work there again. You might -again- live through a phase of euphoria. But you lost your previous “normality” and certainty in doing things smoothly. You might feel like a stranger for some time, followed by uncertainties. Actually, this can be called a return-culture shock, and can be as painful as the first one(s).

In the Euregio Meuse-Rhine, there are about 26,000 cross-border commuters. These people live in two or even three countries at the same time. If you are a cross-border commuter in Germany just for work, your social life remains the same and the culture shock is ‘only’ limited to your work. If you move to Germany and your children go to school in Germany, for example, you will be confronted with more changes and the curve may be steeper. Whether you are only going to work or also to live in Germany, the culture shock normally just passes and, as you say in German: “Alles wird gut”.

Have a nice day and see you tomorrow (day 5)!

By loading the video, you agree to YouTube's privacy policy.

Learn more

Day 5: Communication

Are you ready for this? Today we’re going to be dealing with communication, i.e. the way we speak to each other and get a message across. You guessed it: Here, too, there are differences between Germans and Dutch.

Hidden messages

When we talk to each other, we convey messages. We ask if someone can give us an object, we ask for directions or we want to point out something to someone. We do this not only with words, but also with our facial expression, with gestures and with the tone in which we speak. We call the concrete message the content, for example a water bottle that we want from someone. But in the way we ask, something else comes through: the social relationship with the other person. We call this the relational aspect.

In Germany, it is often enough to add ‘please’ to a substantive question: ‘Please give me the water bottle’ is a polite question in German. That’s all it takes to ask for something or – at work – to instruct someone. No German employee feels insulted by such a request – he or she will simply do it. Germans are, as was mentioned yesterday, very content-oriented, whereas the Dutch are, by comparison, more relationship-oriented.

This difference in communication with Germans is very important and it is important that you know and understand it. Germans have a preference for clear and firm language. This suits the more content oriented and also the more hierarchical relationships within the German work culture.

Clear language

Self-mockery and understatement are very common in the Netherlands to comply with the commandment of modesty. It is not at all unusual to say that you “know only a bit about something”. Within the Dutch context, everyone will understand that you basically mean the opposite and that you know a lot about something. In Germany, such phrases will not get you very far – there is a chance that they will be taken literally! In Germany, self-mockery is more for private contexts – in business life, you call things by their name – no more, but also no less.

“Male” and “female” way of communicating

According to the Dutch cultural scientist Geert Hofstede, Dutch society is particularly feminine, while German society is much more masculine. By this he means that Dutch women and men are expected to be caring, to show emotions and to act modestly. This is also reflected in the way they communicate, for example by using diminutive words (having a little cup of coffee with a colleague and a little biscuit or little cake) and by verbally emphasising how ordinary we are and how comfortable we are. In Germany, the socio-cultural expectations of men and women are different and men in particular are expected to be more assertive and competitive outside the home. The way of communicating is therefore much more direct and straightforward – much more “masculine”.

Do you remember the iceberg on the 1st day of this mini-course? In all the areas that have been discussed over the past few days, you can see a clear difference between visible and invisible aspects of German culture. Visible aspects are, for example, the way of managing and communicating, decision making or status awareness. Invisible are the norms and values that underlie these aspects, such as respect, duty or responsibility. Of course, these values also exist in the Netherlands! However, they are brought to life differently in Germany and have a different priority.

Have a nice day and see you tomorrow (day 6)!

Day 6: Dealing with rules, structures and government agencies Normal 0 false false false DE X-NONE X-NONE /* Style Definitions */ table.MsoNormalTable {mso-style-name:"Normale Tabelle"; mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0; mso-tstyle-colband-size:0; mso-style-noshow:yes; mso-style-priority:99; mso-style-parent:""; mso-padding-alt:0cm 5.4pt 0cm 5.4pt; mso-para-margin-top:0cm; mso-para-margin-right:0cm; mso-para-margin-bottom:8.0pt; mso-para-margin-left:0cm; line-height:107%; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:11.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-ansi-language:DE; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;}

Congratulations, you’re over the halfway mark! Today we’re going to pick out a topic prone to frustrations: Dealing with rules, structures and government agencies in Germany follows a different logic compared to the Netherlands

Heading} Germans like structures and rules – and abide by them

Most people know the story of Germans waiting in empty streets in the middle of the night for a red traffic light. It’s a cliché, but the fact is that rules and regulations are more respected than in the Netherlands. As the German philosopher Kant said, everyone should behave in a way he or she could imagine as a general rule for the whole society (“kategorischer Imperativ”). There is some level of trust in Germany, that rules as such have a legitimation. The sense and nonsense of rules in a specific situation are less readily questioned and there is less room for interpretation.

German bureaucratic procedures can be extremely precise but also lengthy in their way of doing things. It is also much more usual in Germany to record everything, varying from interview notes to entire protocols. These are then of course stored in the extensive archive. Because of this, people in Germany often react less pragmatically than people in the Netherlands are used to and there is less room for flexibility and the well-known Dutch ‘will be fine’. So take this into account when working with Germans and be prepared to meet the greater need for rules and structures.

Ensure a “gründlich” project planning

Planning is not only important when making appointments. When planning a project, Germans are generally more thorough and detailed than the Dutch. While the Dutch prefer to keep all options open for as long as possible – even after the decision-making process – the Germans prefer to consider all eventualities and what should be done in advance. More than the Dutch, Germans try to avoid or reduce uncertainties or risks through good planning. After all, the devil is in the detail! Adjustments due to the Dutch standards of “progressive insight” and an attitude of ‘we’ll figure it out when the time comes’ attitude are not really preferred in Germany. It is better to have a thorough planning to meet the German need for certainty. And oh well, it’s not so bad to analyse and eliminate bottlenecks ahead of time, anyways.

Yet catching up on digitisation

When it comes to digitalisation, Germany lags behind many countries. The laying of glass fibre cables for fast internet is not yet as advanced as in the Netherlands. Especially in the countryside (and there is a lot of countryside in Germany, much more than in the Netherland). The exchange of data via digital systems is also still in its infancy in the business world and especially in government. This has consequences for communication with companies and government agencies – it is not always and everywhere possible to make contact via the Internet. In contact with the government, you will find that you often receive forms by post – which you then have to send back by post. In health care, education and service providers such as banks, digitisation is also lagging behind in comparison to the Netherlands. For example, electronic banking is less common in Germany than in the Netherlands. And the fax machine? In the Netherlands it has become a museum piece, but in German companies and government agencies it is still an important means of communication. Sometimes, companies would even change to more digitalised procedures. But if the authorities they need to communicate with require paperwork, there is little room for manoeuvre. Although there are impressive result of the corona crisis, paper-based bureaucracy has led a strong and lasting mark.

Extra: Background information

In the Dutch collective memory, this country has sailed all seas and got a fortune out of it. Traders from e.g. Hamburg also sailed the seven seas, but in German collective memory, other events are more dominant. Germany is often not at the forefront when it comes to following social and political developments. People do not like uncertainty and often react hesitantly to changes. The two World Wars and the turbulent period in between, with political chaos, mass unemployment and hyperinflation, have become anchored in the German collective memory. This has created a form of fear of the negative consequences of (yet another brute) change. The spying on the population during the war years and in the GDR still leads to a great reluctance to deal with and share digital data. Trying out new things and seeing where it takes you is therefore out of the question. Risks are preferably avoided, for example by strict regulations and detailed planning.

Have a nice day and see you tomorrow (day 7)!

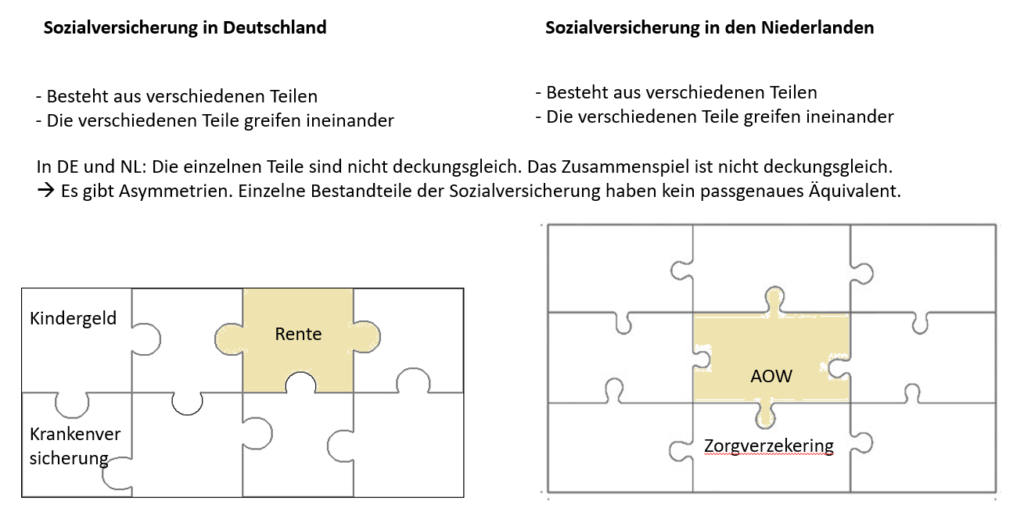

Puzzle-model to explain cross-border asymmetries

Culture is like a puzzle built of various puzzle-pieces. Many puzzle pieces re-occur in every culture, but they often have a different shape or have another context. Across borders, in culture and bureaucracies, there is always an asymmetry.

For example pension: The German “Rente” is an important puzzle-piece of the German social security; such as the Dutch “AOW” is in the Dutch social security system. But both are not fully equivalent, and transferring one to the other leads to some frictions and questions. The Grenzinfopunkte are a free service to facilitate the transfer from one system to another so it fits best for you.

Day 7: Dealing with feedback and conflicts

We are steaming ahead in this 9-day mini-course. Have you come across any factors that are new or unusual for you? Today’s theme is ‘feedback’ and ‘addressing criticism’. A sensitive topic where misunderstandings can quickly arise due to misinterpretations.

Or-or instead of and-and

The Netherlands is a country of compromises, not of sharpers. It’s only logical that sticking to one’s own opinion is not something one wants to see. After all, that leads to arguments and conflicts – which do not fit in with trying to find a solution together. It is different in Germany. The Germans, as has already been mentioned, are more content-focused. German employees are often well educated, have excellent professional knowledge and skills, are analytical and good at thinking up solutions to problems. Logical argumentation is key here. When faced with a problem, Germans look for the best solution rather than the optimum – can you feel the difference? In order to find the best solution, they will not shy away from differences of opinion.

In discussions, Germans will therefore try to impose their opinion – if necessary, with raised voices and emotions. Now, the Dutch discussion culture has also become more emotional in recent years, but Germans are much stricter when it comes to presenting and defending arguments. They do not shy away from technical jargon, as a sign that they take the subject and their discussion partner seriously. To the Dutch, this can come across as pompous, accustomed as they are to “ordinary language”. The German style of discussion is therefore diametrically opposed to the Dutch style, which is primarily aimed at keeping the relationship going. In Germany, however, the status consciousness is higher – also in discussions.

Dealing with mistakes

Do you know the saying “you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs”? You sometimes hear it in a Dutch office environment when someone has made a mistake. The underlying message is that everyone is doing their best, mistakes can happen and are not made on purpose. In Germany, mistakes may not be handled so easily. The German work culture is more perfectionist, the focus is more on content and performance and that has consequences for dealing with errors. The fear of making mistakes is greater in Germany – probably one of the reasons why far fewer companies are set up in Germany than in the Netherlands. Meanwhile in Germany, it has also been recognised that fear of making mistakes can be an inhibiting factor. That is why many organisations and companies are working to deal more pragmatically with mistakes and to introduce a positive ‘Fehlerkultur’, a culture that is open to little risks and prioritises learning from mistakes over avoiding them.

Have a nice day and see you tomorrow (day 8)!

Contacts beyond working hours

Compliments, great that you are still participating and following the training! Hopefully, by now you have gained a lot of valuable knowledge on how to work better with Germans. Today we are going to talk about opportunities for contact outside working hours.

Choose the right social network

There are plenty of Germans with a LinkedIn profile (15 million in Germany, Austria and Switzerland combined), but with over 18.5 million users in the three countries mentioned, Xing is still bigger, especially in the traditional branches. YouTube and Facebook also play the leading role among German social media users, but Twitter plays a minuscule role in Germany, especially in the business world.

Separation of work and private life

At work, many Germans are more reserved and formal and there is less room for emotions and humour. Colleagues are mostly – well, colleagues, and it is less common to invite them to your birthday than in the Netherlands. Conversations are more businesslike and there is less attention for a ‘cosy round of small talk’. Friday afternoon drinks are largely unknown in Germany.

Celebrating a birthday the German way

In contrast to business life: Have you received an invitation to a birthday party at the home of German friends or perhaps a colleague you’ve befriended? This is fun and a great token of appreciation, something that should not be taken for granted.

If you are invited for the evening and you are told that there will be something to eat, you should bring an appetite. Because that “something to eat” usually turns into an extensive barbecue or a buffet with all the trimmings! In short, German birthday parties are more elaborate than Dutch ones – and that also applies to the preparations. To make sure that the birthday boy or girl does not have to spend days in the kitchen, it is quite common, especially among friends, for everyone to contribute to the buffet and bring a salad, dessert or something similar.

When it comes to bringing a present, things stay the same: just like Dutch birthday boys and girls, you can also make German friends or colleagues happy with a bottle of good wine, an original gift voucher or something similar.

Have a nice day and see you tomorrow (final day 9)!

Day 9: The deep dive

The last day of the mini-course has arrived – and with it, the time to wrap up this mini-course. Up to now, we have been dealing with what culture actually is and what cultural differences there are. Today, you will learn about a method that can help you in everyday life to put yourself in someone else’s perspective and check your own representations: DIVE. This abbreviation stands for:

- Describe

- Interpret

- Verify

- Evaluate

So you feel uneasy with the top-down decisions in your company?

Describe what it is that enerves you, and break it down to little pieces to make your gut feeling more concrete.

Interpret what you assume behind the decision-making you see. In you culture, top-down procedures might indicate missing trust towards employees. Here, reasons might be different, and top-down decisions could even try to make your life as an employee easier and in a clear framework.

Verify what you expect behind what you see, or which values you assume below the surface. What do colleagues, friends perceive?

Evaluate your findings and stay open for re-interpreations. As the saying go, especially in the beginning in a new culture: “Be quick to see but slow to judge”

Our advice: in the event of a misunderstanding, first of all assume that the person you are talking to has good intentions. Consider whether cultural differences can play a role. If so, try the DIVE method and see if you can come to a different understanding.

This brings us to the end of this mini-course. We hope you have gained many useful insights. Although this mini-course focused on cultural differences, it is worth broadening your perspective and “zooming out”. As you look the Netherlands and Germany from a distance, you will see that both countries are sometimes very similar, for example in terms of work mentality, punctuality or organisation. If you have to deal with a – hopefully mild – culture shock at the start, then looking at the similarities can help you put everything into perspective and find something to hold on to.

And now: applause! You have worked through the days and learned a lot about the German way of cooperating and communicating. That is worth a compliment!

We wish you viel Glück in Germany and say “Tschüss” from Aachen!

Texts by Ingeborg Lindhoud for GrenzInfoPunkt Aachen-Eurode at Region Aachen Zweckverband. All rights reserved.